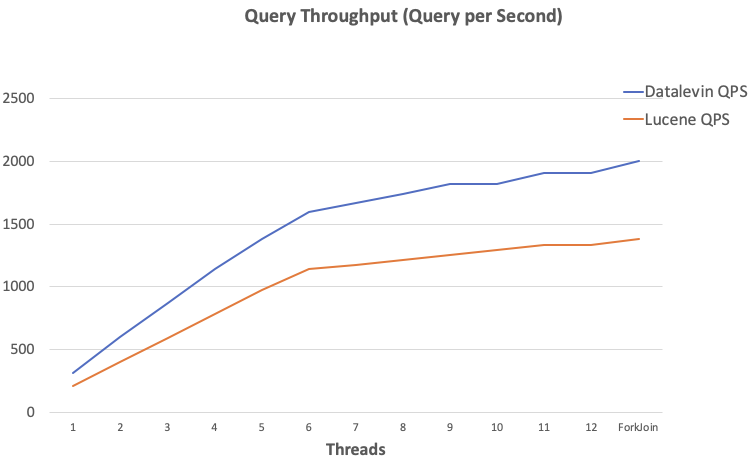

Here is the story. I am adding full-text search capability to Datalevin, a Datalog database that we open sourced last year. For this task, I have decided to write a search engine from scratch instead of using an existing search library. Here are some rationales for this decision. Today I finished the main work of the search engine, and ran some benchmark comparison with Apache Lucene, the venerable Java search library, and found that the Datalevin search engine is 75% faster on average than Lucene, while 3 times faster at the median point. Since Lucene is at such a dominant position in full-text search, I think it might be of broad interest to write about it.

Yes, it is true. The search engine is less than 600 lines of Clojure code.

Lucene is Hard to Beat

Lucene has over 20 years of history, with perhaps hundreds of man-year of work behind her development. Any search engine coming out with better numbers than Lucene is suspicious of dishonesty, incompetence in benchmarking, or both. I will not name names, but a Google search should show some samples of these. Obviously, I would not want to add Datalevin to such a hall of shame. Please do report any errors in my benchmarking.

Better Search Algorithm

To beat Lucene, it is obviously not enough to optimize code, as Lucene is highly optimized to the last fine details. For example, Lucene has multiple versions of Priority Queue implementations, each customized to a different use case. It is insane.

So, to beat Lucene, having better algorithm is pretty much a requirement. Luckily, I did come up with a better search algorithm, which I call T-Wand.

By "better", I mean it in two senses.

Better Relevance

How many time have you felt frustrated that the search engine gave you results that you know are worse than what you should be getting?

I know there are some documents containing all these words, why are they not here?

"Here" means the first page, or being in the "top-K" results in research parlance. Full text search engines, like Lucene, are often optimized to return a limited number (K) of good results as quickly as possible. However, what is a "good" result? This is where the concept gets muddier. It is no longer a purely technical problem, but more of a user experience problem. In research parlance, this is called "relevance".

As someone who has a Ph.D. in Human-computer Interaction ;-), I feel like I am entitled to define a condition of "good" in relevance here. I hereby declare that:

A good top-K algorithm should rank a document containing more user query terms higher than a document containing less number of user query terms.

This makes perfect sense. Right?

Right. Unfortunately, most search engines, including Lucene, do not do that.

Most search engines use something called a vector space model, where both user queries and documents are reduced to vectors (i.e. a fixed number of numbers). That is to say, the search engines are not looking at the meanings of the queries or the documents. Instead, they turned them both into some numbers. The search problem, is reduced to a problem of finding the similarity between the numbers representing the query and the numbers representing the documents.

An often used similarity measure, is to treat these numbers as coordinates in some kind of space. Now both a query and a document become vectors (or points) in this space. And if you remember any of the high school math, you will know that one can calculate the angle between a query vector and a document vector. This angle is the similarity search engines use to rank the relevance of documents to the query. The smaller is the angle, the higher ranking is a document.

This is an elegant model. However, as you can see, this vector space model does not explicitly require a higher ranking document to contain more query terms than a lower ranking one. The results often come out violating the above requirement, inducing user frustrations. This is a well-known problem. For example, Lucene 3.5.0 (when they were still humble enough to write this?) introduced its scoring features with this paragraph:

Lucene scoring is the heart of why we all love Lucene. It is blazingly fast and it hides almost all of the complexity from the user. In a nutshell, it works. At least, that is, until it doesn't work, or doesn't work as one would expect it to work. Then we are left digging into Lucene internals or asking for help on java-user@lucene.apache.org to figure out why a document with five of our query terms scores lower than a different document with only one of the query terms.

T-Wand wants to change that.

Better Search Speed

T of T-Wand stands for Tiered. As you might have guessed, our search algorithm divides the document collections into tiers. The first tier are those documents containing all n user query terms, the second tier are those containing n-1 user query terms, so on and so forth.

With this division, we no longer need to consider the whole document collection as the potential result candidates. Instead, only those in the current tier are. With much less work to do, the search speed is going to be better.

T-Wand Algorithm

First, let me introduce the WAND algorithm.

WAND

Did I say Lucene is fast? Lucene is very fast, because it uses one of the state of art search algorithms, WAND [1]. Here's how WAND works.

It cheats.

Well, any sufficiently advanced algorithm looks like cheating. WAND is no exception. Basically, it skips a large portion of document collection, and it skips them safely, meaning the results would be the same if one exhaustively does the full computation without skipping. It is able to safely skip documents by using two tricks.

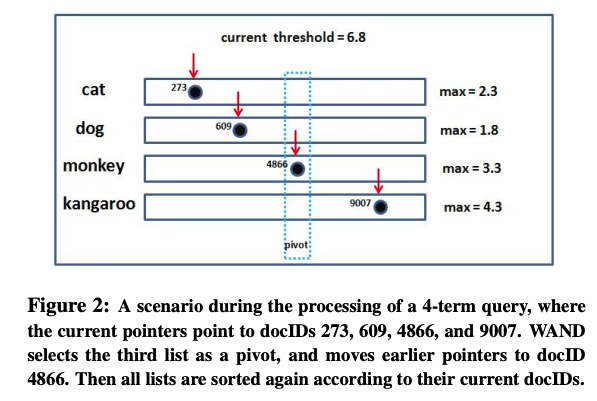

The first trick is the most ingenious. I still do not know how my former colleagues at IBM Research came up with it. My hat's off to them. Let me steal a picture from a followup article [2] to illustrate this.

As can be seen, the 4 rows are the document ids of 4 query terms, and four iterators are walking the document ids from left to right. At each step of the iteration, WAND arranges the rows such that the current document ids of the rows are sorted from lower to higher.

Now, starting from the first row, we sum up a maximal "goodness" score of that row's documents, as soon as the "goodness" score pass a certain threshold, we stop at that row. Say, this row is the 3rd one. At this point, we can teleport the first two rows's iterators to the document ids where the 3rd one is at, skipping every documents in between. This skipping is safe, because, by definition, the document pointed by the 3rd iterator is the first one that pass the threshold. Those before it would not have passed, because the "goodness" scores we use for each row are the maximal of those rows. There could not possibly be anything larger in those skipped documents.

As we have alluded to, the second trick, is this idea of using a hypothetical maximal possible score to filter out potential candidates without having to fully examine them: "we already gave you all the slack possible, yet you still cannot pass the bar, so we can safely kick you out without having to look at you in details". This is a fairly general idea that is used in many algorithms. For example, I would consider A* algorithm is in the same spirit. This reminds me also of a Chinese strategic doctrine, "料敌从宽“, it means to estimate the strength of the opponent in the most generous term possible, and to plan accordingly.

In WAND, the threshold used to filter out documents is the current lowest score of those documents that have made into the top-K. This threshold becomes more difficulty to pass as the algorithm proceeds, filtering out greater proportion of documents as it goes.

What's New in T-WAND

So it seems to be obvious to apply the same WAND algorithm in each tier. But that would not be efficient, because now you are going to have multiple passes over the document collection, doing a lot of wasted work.

Another idea came into play, which was actually the first idea I tried. This idea was inspired by an idea in another research field, approximate string matching [3]. In retrospect, this idea has the same element of "giving your enemy maximal possible slack" spirit.

Here, to establish the maximum and the threshold, a little bit math is involved. I will spare you any formalism, because the actual idea is very simple, some would say trivial.

Let us start with a special case. Say, we want to find documents that contain all n user query terms, what are those documents?

They must be those documents that contain the rarest term in the user query. Right? Regardless of how rare a term is, a document must have it to meet our requirement of containing all query terms. In fact, the document must contain any one of the given query terms. In other words, it is necessary and sufficient to use any one term's set of containing documents as the candidates, and we can then proceed to check these candidates to see if they also contain other query terms. Since picking any one term would be the same, we will choose the rarest term, for its containing document list is the shortest. All other documents can be safely skipped. Magic, yes?

Generalizing this special case, to find documents containing n-1 query terms, we only need to pick as candidates those documents containing the rarest OR the second rarest term, i.e. the union of them. All the rest of the documents can be safely ignored. Isn't this nice?

We can continue this all the way down to needing only one query term in the document. At this point, every document containing any query term becomes a potential candidate. This reverts back to the difficult problem of searching all matching documents, which WAND solves by skipping documents that are not going to make into top-K.

But we can do much better. Because the above mathematical property also allows us to skip documents that are not going to have the required number of overlaps with the query.

Say we are at a tier that requires t overlaps between a document and a query. We are walking a document candidate down the term rows, trying to find out how many terms this candidate hits. If this candidate has already hit h terms so far, and is now on row k. If we give this candidate maximal slack, meaning that we assume he will hit all the remaining terms, his hypothetical maximal hits would be h + (n - k - 1). If this number is less than t, he can be safely kicked out, because he will never make into the exclusive t club.

This new pruning condition is the main novelty of T-Wand in term of algorithm, as it has not been reported in the literature for search algorithms, as far as I can tell. With this pruning condition and candidate pre-filtering, we can already achieve about 65% overall speed of Lucene. Adding the pruning condition of WAND, we have the current T-Wand performance, which beats Lucene with ease.

Implementation Takeaways

I said beating Lucene with ease, because we did not do any extreme optimizations that are abundant in Lucene. Our code is idiomatic Clojure, with some additional help of Java data structures at critical performance hotspots. The code weights less than 600 lines, including comments.

Clojure

So why use Clojure? The short answer is that it makes programming fun.

It is fun to explore ideas with the language. One little known fact that I found about using Clojure, is that it is an excellent language for implementing published algorithms in academic papers. Most algorithmic papers include pseudo code, written in an imperative programming style. They seem to be a far cry from any functional programming code one would write.

However, I found the opposite to be true. It is easier to translate published imperative pseudo code into functional programming real code, than trying to turn imperative pseudo code into imperative real code. Looking at any code repository accompanying a paper, the imperative programming code in the repository bears no resemblance to the nice pseudo code shown in the paper.

With a functional programming language, on the other hand, the resulting real code will have a one-to-one correspondence with the pseudo code. If you know Clojure, you can look at my code of T-Wand, see the similarity between my function score-docs and the pseudo code in [4]. I just gave each code block in the pseudo code a name and turns that into a function, find-pivot, score-pivot, next-candidates, etc. The function realizes the intention and logic of the pseudo code, but not following its style. The code is easy to follow and change, allowing exploration of many ideas.

The current form of T-Wand is the result of at least three major iterations of ideas, first the candidate pruning by required overlaps idea, then candidate pre-filtering idea, finally incorporated both into T-Wand. All these changes and refactoring were done with great ease, with a sense of adventure and fun. I can not imagine how painful this would be to iterate these ideas on a statically typed language and in an imperative programming style. I probably would just give up.

Index Storage

In Datalevin search engine, we store the primary data structure for searching in LMDB in an aggregated form, as a sparse integer list. The reason to store and access term information in aggregates, instead of storing them in inverted lists and accessed piece-meal, is because LMDB is very efficient (more efficient than file systems) at reading/writing large binary blobs.

As long as the data structure to be stored has high (de)serialization speed, it is more efficient to store/retrieve them in large aggregates than in more granular forms. This does not apply to more complex data structures with high construction cost, such as hash maps. We consider these as general advises on how to best use the so called single-level storage, such as LMDB. We earned these lessons in our many iterations of trying to find the best performing indexing data structure.

Conclusion

I am happy that this exploration turns out well. I would be thrilled to see T-Wand algorithm makes into other search engines, as it does improve user experience, performs well, and it is simple to implement in existing code bases that use WAND. There are many more ideas of improvement can be further explored, I would be happy to have a collaboration if someone wants to take it further.

Updates for Hacker News People

For people who are worried, please be assured that T-Wand also uses

tf-idf and the vector space model, so you are not missing anything fundamental.

For people who say "Lucene is not properly used", please write the proper Lucene code in one of the issues, in Java if you want, I can integrate them into the benchmark. If you know Clojure, just send a PR. I appreciate that. Better yet, if you know Lucene so well, you should send a PR to Lucene that integrates T-Wand into Lucene, that would make the biggest impact.

For people who say "Does yours have all the Lucene features - stemming, incremental index, phrase search, range search, arbitrary sortable fields, etc?", at the moment, the following features are implemented:

-

Core search capability

-

English analyzer

-

Incremental and bulk indexing

The following are to be implemented in the future:

-

Fuzzy query matching

-

Stemming

-

Phrase search

-

Boolean operators

The followings are not necessary because Datalevin is a real database and it has more powerful database features than whatever a search engine can offer:

-

Range query is a foundation of Datalevin database

-

Fields are just watered-down columns in a database. Datalevin is a fully featured database. Whatever you want to do with fields, you can do with Datalog.

I am opening up for feature suggestions. Please file issues or send PR. I appreciate them.

Finally, please do not misunderstand what is going on here: I am running a startup, and I am also old enough to not care about publications as much as much as people who are younger or in academia. That's why I chose to reveal this in a blog post instead of hiding it until after my paper is published. A blog post can reach more people then an academic paper can.

References

[1] Broder, Carmel, Herscovici, Soffer and Zien, Efficient Query Evaluation using a Two-Level Retrieval Process, CIKM'2003.

[2] Ding and Suel. Faster top-k document retrieval using block-max indexes. SIGIR'2011.

[3] Okazaki and Tsujii, Simple and Efficient Algorithm for Approximate Dictionary Matching. COLING '2010.

[4] Crane, et al. A comparison of document-at-a-time and score-at-a-time query evaluation. WSDM' 2017.

yyhh.org

yyhh.org

Comments